Sonny Jurgensen learned he had been traded from the Philadelphia Eagles to the team now known as the Washington Commanders while eating lunch on April 1, 1964. He thought it was an April Fool's prank.

Jurgensen had been in the NFL for seven seasons, all with the Eagles. He had been their starter for the last three years and had led the league in total passing yards in two of them. In 1961, he also led the league in touchdowns.

But Philadelphia had fallen off in 1962 and ’63. Jurgensen was seen as too much of a swashbuckler. A risk-taker. Sure, he threw 54 touchdowns in 1961 and ’62 — an outstanding total for the era. But he also tossed 50 interceptions in the same two years.

When he struggled with an injury in 1963, the brass in Philadelphia began looking to move on. Washington had a promising young signal-caller named Norm Snead, whom they were willing to part with for a chance to grab a mercurial talent like Jurgensen.

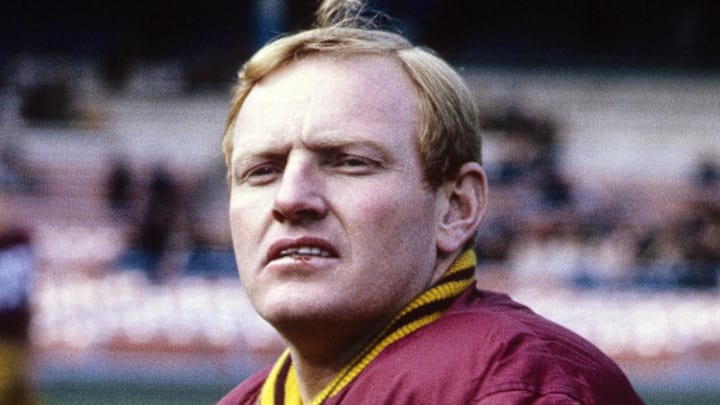

Sonny Jurgensen was the embodiment of everything great about Washington football

And so it came to pass that Jurgensen was sitting in a deli eating lunch when he found out he would have a new NFL home.

Jurgensen died on Friday at the age of 91. His legacy in both the league and Washington is secure. The Pro Football Hall of Fame. The Ring of Honor. More than 50 years after he took his last snap for Washington, he remains one of the two or three most beloved players in franchise history.

Watching your childhood heroes grow old and die is one of the most concrete markers of our own mortality. I’ve had to write a lot of these tributes in recent years. For each — from Bobby Mitchell to Charley Taylor to Pat Fischer — I have gone back and read up on them via contemporaneous accounts from their playing days. Even though I remembered them quite well, I wanted to check my facts. Memory is a shifting thing.

But with Jurgensen, I barely felt the need to do it.

It was a long time ago, but it felt like last week. Jurgensen predicted modern NFL offenses before Don Coryell, Bill Walsh, or the greatest show on turf. He threw the ball short. He threw the ball long. He threw a prettier ball than any quarterback ever had.

Jurgensen, Dan Marino, and Aaron Rodgers. That’s my list of the greatest pure passers to ever launch a spiral in an NFL game. Order them however you want. Add a fourth if you want a Mount Rushmore. But No. 9 is on that list.

He had an odd windmill delivery that could effortlessly deliver deep balls, fire line drives on a deep out, or put the most feathery of touches on screens. Jurgensen could make every standard throw, and he was also flipping the ball underhand or behind his back decades before Patrick Mahomes was born.

The numbers speak for themselves. In the late ‘60s, while in Washington, he led the league in passing in three of four seasons, throwing for more than 3,000 yards each year. This was when the season was just 14 games, and rules allowed defenders to massacre receivers and quarterbacks alike. Illegal blow to the head? Deacon Jones would have two of those in the first series of the game.

But Jurgensen's impact cannot be captured in his numbers. To understand that, you have to recognize what Washington football was like in the years before he arrived.

In short, it was a train wreck. Several decades earlier, with their first revolutionary quarterback, Sammy Baugh, flinging the ball, the franchise was among the league’s elites. But by the mid ‘60s, it had been almost two decades of awful football. The fans remained loyal, but the team was wretched.

Those two things were linked. Because he never lost fan support, owner George Preston Marshall could justify his racist policy of fielding a whites-only team, even if it meant the on-field play suffered. He was forced by governmental action to segregate his roster in the early 1960s — the last NFL owner to do so. Things began to turn around with Bobby Mitchell's arrival in 1962.

Two years later, the same year Jurgensen walked into a Philadelphia deli as an Eagle and left as a member of the Washington team, Charley Taylor arrived. And in 1965, Jerry Smith came to town.

Jurgensen, Mitchel, Taylor, and Smith put on a show like the league had never seen before. In 1967, Washington’s three primary receivers finished first, second, and fourth in the league in receiving yards. The quarterback threw more passes, had more completions, and piled up more yards that year than any signal-caller in NFL history to that point.

The defense was still atrocious. Washington never won many games in those years. But they were the most exciting team in the league. The energy at D.C. Stadium back in the day was palpable. The modern legend was formed in those years.

Of all the great “what might have beens” in local sports history, few are as tantalizing as what happened in 1969/70 to Jurgensen and the team. Vince Lombardi came to town in 1969. The gunslinger had some decent coaches throughout his career. But now, he would be teamed with the very best.

There was some talk at the time that the straight-laced coach and his fun-loving quarterback would be like oil and water. You see, it was fairly well known that Jurgensen did like to break curfew and go for a drink on occasion. Those concerns underestimated both the coach and the player.

Lombardi wanted to win, and he knew Jurgensen was a rare talent. The player also wanted to win, and he knew this coach was his best chance. They came together for a very good 1970 season — posting Washington’s first winning record in over a decade.

Then cancer ended Lombardi’s life. George Allen eventually came to town. As fine a coach as he was, he did in fact bristle at Jurgensen’s free-wheeling ways. Besides, by this point, the quarterback was hitting his late 30s, and his body was wearing down. Injuries kept him in and out of the lineup over his final years.

But the fans never stopped adoring him. That made things tough on his successor and good friend, Billy Kilmer. The Sonny-Billy controversy divided fans for several years, even as the new man under center led the club to its first Super Bowl appearance in 1972.

After he retired in 1974, Jurgensen became a fixture in the radio booth. He developed a magnificent rapport with former teammate Sam Huff.

Huff had come to Washington the same year as Jurgensen. They worked together for many years in the broadcast booth with Huff constantly overreacting to anything that reflected poorly on the defense, and Sonny patiently correcting his friend.

Like all great quarterbacks, Jurgensen could tell you the play before it ever happened. And he could explain why it worked or didn’t work better than any coach.

The best Sonny-Sam story comes from their early years as teammates, and it is usually told to reflect on Huff’s competitiveness. He hated the New York Giants’ head coach, Allie Sherman, for trading him in 1964. He always wanted revenge.

In 1966, the Giants were abysmal. Late in the game, with just seconds remaining, Washington led 69-41. They had the ball deep in New York territory and were just running out the clock.

Then, a timeout was called, and the field goal team came on. The short kick made the final score 72-41. It set a new record for most points scored in an NFL game. Huff later admitted that he was the one who called time and sent the field goal team on. He wanted to humiliate Sherman.

What gets lost in the story is that Jurgensen and his offense put up 69 points prior to those final seconds. It was Huff’s defense that was playing atrocious football that day. In the middle of the game, with Washington in front 49-41, the quarterback asked a sheepish Huff how many points he needed to score to ensure a victory. He just told him to keep scoring. And that’s just what the legendary figure did.

When you watched Jurgensen back in those days, you got that same feeling you got from all the greats — from Johnny Unitas to Joe Montana, John Elway to Tom Brady, Peyton Manning to Patrick Mahomes. Most of the time he stepped onto a football field, it seemed as if he could have scored at will.

Jurgensen never really played on a great team. If he did, he was too far along to take advantage. But he transcended all that in the hearts of Washington football fans.

How good was he? We’ll leave the final judgment to the man with his name on the league’s championship trophy.

Before he died, Lombardi saw his long-time friend Pat Peppler. He had worked withthe coach as a personnel guy during those Green Bay Packers' championship seasons in the mid-60s.

Lombardi told Peppler, “If we would have had Sonny Jurgensen in Green Bay, we’d never have lost a game.”

There simply is no higher praise for a football player imaginable.