The Washington Football Team has had eleven head coaches – full-time or interim – since Joe Gibbs retired for the first time in 1993.

Ten of those coaches have compiled losing records during their Washington Football Team tenure. That list includes Gibbs in his second go-round and Super Bowl winner Mike Shanahan. It includes current coach and potential savior Ron Rivera and collegiate champion Steve Spurrier.

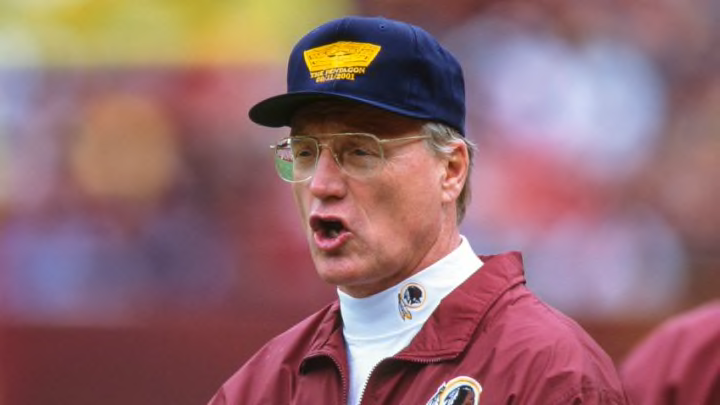

There is only one man who has thus far escaped this fate, and he passed away earlier this month. He passed away with surprisingly little fanfare, especially considering that he ranks in the top-ten of all-time coaching victories. I had intended to write something about him sooner than this. But something always seemed to get in the way.

Something always seemed to get in the way throughout Marty Schottenheimer’s career.

Often, it was the Denver Broncos. Sometimes it was an ill-timed fumble. Or a missed field goal by a normally-reliable kicker. Then, equally often, it was Schottenheimer’s own stubbornness.

Marty coached the Washington Football Team for one season, back in 2001. He was Daniel Snyder’s first head-coaching hire, after getting rid of Norv Turner, whom he inherited when he took control of the team.

His long-term impact in Washington seems negligible. I look at him now as the canary in the coal mine, though few of us saw that at the time. He was proof that the new owner was, at least in his early days, a toxic presence, making decisions based on whim and marketing, rather than on genuine football criteria.

Marty’s career was marked by one overwhelming contrast. Coaching in all or part 21 NFL seasons, he won over 60% of his regular season games, took his teams to the playoffs 13 times, and only had two losing seasons. That is an extraordinary record that ranks with the greatest coaches of all-time.

Yet Marty was never one for sugar-coating, and there is no way to sugar-coat his abysmal playoff record. His teams went 5-13 in the playoffs, never making it to a Super Bowl. His last four playoff exits came when his team (twice, Kansas City, and twice, San Diego) was the higher seed.

Marty always favored a conservative style of offense, and that often resulted in tight games. In one game, Lin Elliott missed three field goals and Kansas City fell 10-7 to Indianapolis. In a devastating loss in 2007, one of Marty’s players, Marlon McCree, intercepted a fourth-down pass instead of simply knocking the ball down. McCree tried to run with the pick but fumbled, giving the ball back to the other team for a crucial fourth-quarter drive.

The quarterback on the other team was named Brady. Marty’s Chargers had nine Pro Bowlers that year, but they couldn’t get past their first playoff game. It was the last playoff game he would ever coach.

Marty came to the Washington Football Team after four and a half years in Cleveland and ten years in KC. He had been in the playoffs in eleven of those seasons. After departing KC, he did broadcast work for a few years, and in that capacity, he had been highly critical of Daniel Snyder – especially regarding his decision to fire Norv Turner.

When Snyder announced Schottenheimer’s hiring, there was hope that this new owner was proving to be a man who did not hold grudges. A man who could look past healthy criticism in an effort to bring in quality football professionals to run his team. That hope proved to be misplaced. After one tumultuous season, there was a power struggle between owner and coach over player personnel authority. Not surprisingly, the owner won the struggle and Marty was fired.

That 2001 season showcased the best and the worst in Marty. He instilled a discipline in the team that had diminished under the more mild-mannered Turner. He refused to overpay for big names, as Snyder had famously done one year earlier.

Whereas 2000 saw the arrival of Bruce Smith, Deion Sanders, and Jeff George, the biggest name Marty brought in was the injury-plagued former No. 1 draft pick Ki-Jana Carter. Best of all, Marty ran a professional operation, one in which he tried his best to handle grievances (and there were plenty) in open locker room conversations as opposed to via unnamed sources in the local media.

But Marty also made plenty of odd personnel decisions. He got rid of productive running back Larry Centers when Centers questioned Marty’s grueling pre-season regimen. Most egregiously, he simply ignored the quarterback spot, seeming to believe that Jeff George could provide what he wanted in a signal-caller, when it was clear to most observers that this relationship would never work.

Sure enough, with an ineffective George and a roster still getting accustomed to a new level of discipline, the Washington Football Team opened the season with a dismal stretch of games. On opening day, they lost 30-3 to San Diego. That was the closest they would come to a victory in the first three weeks of the season. By the time they fell to the previously-winless Dallas Cowboys in Week 5, Marty Schottenheimer stood at 0-5, and his tenure in Washington seemed on life support.

But the Washington Football Team had a history with coaches opening their first seasons at 0-5. Snyder knew that Joe Gibbs had the same record 20 years earlier when he took over as head coach. Snyder gave Marty time, and Marty, as he almost always did, turned things around. Washington won its next five to briefly figure into the playoff race.

The win streak wouldn’t last. Tony Banks, who eventually replaced George as QB, was largely feeling his way through games. With the exception of running back Stephen Davis, there was very little in the way of offensive firepower. But Schottenheimer never coached quitters. Washington was up and down, but when the year ended, they stood at 8-8 – 8-3 in their last eleven games. Just like Joe Gibbs had been.

But the Snyder-Schottenheimer pairing was destined to fail. Neither was going to give in on what they envisioned for the future of the franchise. Snyder intended to bring in a general manager in 2002. The new GM would take a bigger role in personnel decisions, allowing Marty to concentrate on coaching. On the surface, this was a laudable goal. But Marty feared – with good reason, it turns out – that any GM Snyder would bring on board would simply serve as a mouthpiece for the owner. The days of free-spending on big names would return.

In the end, it came down to a difference of opinion. Marty felt he had been hired with the assurance that he would have control over personnel. Snyder felt that, as owner, he was entitled to change course at any point. Dan Snyder won the debate.

Marty would spend his final NFL years coaching in San Diego, doing what he had always done. He won big in the regular season. He lost big in the playoffs.

As for Snyder, his decision to move on from Marty Schottenheimer was not necessarily a bad one. His enormous mistakes came in the aftermath of that decision. He brought back the sycophantic Vinny Cerrato – whom Marty had jettisoned shortly after becoming head coach a year before – to run player personnel, and he hired college coach Steve Spurrier – the shiniest toy on the shelf at the time – to become Washington’s new coach. The disciplined, professional days of Marty Schottenheimer were erased in an instant. The fun-loving, toss-the-ball-around-the-field days of the ball coach were at hand.

No Washington Football Team head coach has posted a career winning record of .500 or above since.

But if Marty was truly the canary in the coal mine, there is plenty of reason for optimism today. The similarities between Marty’s 2001 season and Ron Rivera’s 2020 season are obvious. In both cases, veteran defensive-minded coaches took over teams that had seemed to lose discipline after several years under a more laid-back offensive-minded coach. Both coaches faced major issues at quarterback and had a general dearth of offensive talent with which to work. Both coaches began the season disastrously.

Yet both coaches never let their players give up and after those dismal beginnings, seemingly willed their teams to victory. This time, the owner seems to have learned something. This time, the coach isn’t going anywhere. This time, the new front office personnel are in lockstep with the coach’s agenda.

This time, the owner appears to be willing to stay on the path of slow and steady progress, even though it may not garner the most headlines or feature prominently in the national media. And maybe – just maybe – he’s doing all that because he is remembering twenty years ago, when he had a genuine professional football man on his payroll, and couldn’t figure out what to do with him.

Marty’s time in the NFL was long and largely under-valued. His time in Washington was brief and largely forgotten. Now that he is gone, it may be time to reevaluate both those legacies.